On writing obituaries

Death notices offer a final burst of life

Twice in two weeks I have had to think about obituaries.

Some people - many, it seems - think about them every day, for the death notices are some of the best read pages in most newspapers. Sports, scandal and gossip, world news: all this you can get on the Internet, and people do, but newsprint still seems to be the favored medium for carrying obituaries. It could well be the only thing that keeps newspapers from crumpling under the weight of the Internet. I live in Europe and the people whose deaths interest me tend to be in English-speaking countries, but I do read the Swiss death notices, in French, about people I don't know.

I live in Europe and the people whose deaths interest me tend to be in English-speaking countries, but I do read the Swiss death notices, in French, about people I don't know.

Sometimes I read French obituaries, from France, and feel I know those people even less, but I have always felt that way about the French, who remain an enigma to some of us despite spending years there.

I don't, however, read obituaries every day. This is not out of a fear of morbidity, but rather a worry that I will be pulled in too far.

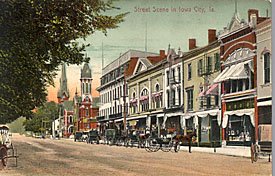

The last time I read obituaries was three weeks ago, before I was obliged to think about them, and most unusually I read them on the Internet. I was doing research for my sisters, who wondered about the accuracy of my aging mother's memories of a murder in Iowa in her youth that might or might not have involved the family of the owner of my grandfather's drugstore premises. Try plugging those search terms into the Internet. Ouf! as people here say. photo, Iowa City, 1907: University of Iowa Hospitals, Bob Hibbs, Iowa City Citizen Press

photo, Iowa City, 1907: University of Iowa Hospitals, Bob Hibbs, Iowa City Citizen Press

I found an obituary, not quite the right one, but interesting, from the end of the 19th century. From that I learned about a murder, again not the right one, but in Iowa a few years before my mother's birth in 1912. I read the lurid newspaper reports on the murder and trial, and couldn't stop before learning about the acquittal. The wife was judged to be "not in possession of her wits", or something similar. It was stated that this problem was relatively common in women of her age, 43. So from the husband's obituary to the trial I had to find out what happened to the wife.

She lived to a ripe old age in Iowa, making rag rugs. Her offspring said that as an old lady she was a quiet person. I saw a photo of her grave, which gives no hint of a life of drama, compliments of the state web site on graveyards. I learned that one of her sons was decorated in the Spanish-American war, to which he ran off shortly after the murder and trial. He lived to invent and register the patent for a fly trap that would neatly kill your flies. Since we live too close to a Swiss farm with lovely cows that attract flies I read the details of the flytrap with great interest.

And since I was searching for murders in Iowa I was referred by search engines to dozens of obituary pages, where I learned that Iowa was a more exciting place than I had thought, growing up. I had to set up a folder on my computer desktop called "Iowa murders" to keep the threads together, in case I want to read more later. One of the useful sources is an industry publication called Grave News.

I still had not been obliged to think about writing obituaries when I found myself reading more of them. An added search to verify family sagas was based on a comment my mother let fall to one of my sisters. We wanted to learn if a cousin of my mother's had really been involved in a financial scandal, as she seemed to hint. He had apparently died years ago. In fact, the Waterloo Courier obituaries showed that he died only last September, well into his 90s. It turns out that he, too, was a decorated war hero and considered an upright and even leading citizen to his dying day.

While reading the Waterloo paper's death notices from a few months ago I turned to the current ones. There I found two women in their early thirties who had died young, from complications linked to disabilities. I have a 13 year old daughter with severe disabilities, and thinking about these families and the complicated emotions they must have been dealing with took my breath away. I paused for a while and thought about them, wondered about their lives.

I read on. I was startled to learn that a Mr. Babbitt had died in Waterloo. He, too, was in his 90s. Iowans seem to live long lives, as often as not.

I remembered my mother telling me a story about Sinclair Lewis when I was off at college studying literature and reading his books. Lewis, a journalist and novelist, did a short stint at a newspaper in Waterloo, perhaps the Courier. My mother's brother worked in Waterloo and said nobody thought much of the unpleasant redhead. At that point Lewis had made a name for himself with Main Street, published in 1920, and it's possible that Midwesterners, depicted as small-minded in his novel, did not warm to the man. In 1922 he published Babbitt, which I had always assumed was a made-up name.

To discover that there really were Babbitts in Waterloo, where he worked at some point, made me wonder if the writer had met the family of the man who died last month. Even more exciting to the newly discovered literary sleuth in me, was reading in the obituary that Mr. Babbitt spent his adult life working at the Rath meat packing plant, for which Waterloo was long famous. I thought I remembered something about the sins of the meat packing industry in his books.

Alas for the sleuth in me, what I discovered by doing basic research is that I was confounding two American writers, both of whose work I enjoyed as a student: Sinclair Lewis and Upton Sinclair. Sinclair Lewis, from the Midwest, wrote about people and towns there and changes in American society after World War I. In 1927 he published Elmer Gantry, probably the book that came out after his Waterloo days, when my uncle would have been 17. Three years later he won a Pulitzer for his novels and their contribution to American literature. Citizens of Iowa, or many of them, were not impressed.

Upton Sinclair was born into a formerly wealthy family in Balitmore. He wrote nearly 100 books, the best known of which was probably The Jungle, an expose of the Chicago meat-packing industry and a gruesome read.

The sleuth in me was quietly retired, but I am grateful to Mr. Babbitt in Waterloo for reminding me that we often remember imperfectly the things we learn in school.

Little work was done that day.

I was obliged to think about writing obituaries during a writing course that I teach to university students. They come from around the world and their English is not always strong. They are 18-20 years old. I gave them samples of writing from the Bulwer-Lytton bad writing contest and asked them to identify elements of bad writing. Someone offered this: "They use obscure words, like obituary." The others agreed. Only one person in the class knew what obituary meant and they wanted to know where the word came from. I was startled that they didn't know the word, but reminded myself that they are young and death seems like an event far in the future. I floundered, said it must come from Latin, which none of them have studied. I looked it up at home: from medieval Latin, from obitus, or death.

The second reason I have had to think about obituaries is that I have been asked to write one. My sisters have asked me to write about our mother, who is 94 and fading rapidly. As the doctor put it: she appears to be shutting down. I wish she weren't, of course, and I wish that I could discuss her obituary with her - she has always been a no-nonsense person. I wish we had written most of it together five years ago when her sharp humor would have poked holes in anything maudlin that might creep in.

My sister Mary summed up nicely why we care about obituaries. "We all think it would be great to have one that goes beyond just a dry recitation of facts and somehow captures what Mother was really all about. Sometimes I read the most wonderful obits in the paper; in fact, I've gotten kind of hooked on reading them! Now and then there's a standout that makes me wish I could have known that person."

A laudable goal in life, it seems to me (and I learned this from my mother) is to have a positive impact on others. It might be on a large scale - I am currenly reading the autobiograpy of Washington Post owner Katherine Graham, inching my way through 625 pages of Personal History that shows just how much impact one woman can have.

It is more often small scale, but equally important. Good individuals who encourage a couple other people to be good individuals strengthen the fabric of society.

My mother was a very ordinary good person who lived in a very ordinary world, and that is extraordinarily special.

To better reflect on what to say, how to capture rather than summarize a life well lived, I did a little research this morning. Here is a sampling of the obituaries I found today, two recent and two not. They make me wish I had had a chance to ask these people a few questions.

Allen Walker Read, etymologist who sought the origin of "OK"

Phyllis Benham, of Reinbeck, Iowa, older than my mother and who taught school for more than 50 years

Charles Yeschke, FBI agent, father, tree trimmer (impressivley written by a student reporter)

Hunter S. Thompson, wild man journalist.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home